How Things Work

Things are different in Cuba. Different enough that some of them need to be explained.

The Internet

Cuba opened up to a largely uncensored internet in 2015, with private wifi becoming available in 2019. They’re still not keen on pornography, terrorism, and, curiously, satanism, but they don’t appear to limit access to news sites or prohibit the downloading of files. It’s now possible to rent a casa particular through airbnb that includes wifi. But that doesn’t mean what you think it means.

Having a wifi router in Cuba, in either a rental or your own home, is a big deal. Not everyone can get one, as there has to be a spare, dedicated phone line in your unit, and it has to be up to ETECSA (the state-owned telecom) standards for data. If you don’t meet those requirements now, it can be a long wait to have ETECSA upgrade your line. Our local friend Jenn told us it took her four years to get an upgraded line installed.

And there’s no such thing as broadband, as the connectivity is through standard copper phone lines. What’s provided is just the pipe, not the data. It’s as if Comcast provided the cable modem and Charter provided the data plan that was available through that modem. It’s just that in Cuba, both of those providers are ETECSA.

If your apartment doesn’t have a wifi router, there are public wifi hotspots. Parks and government buildings tend to have public wifi. That’s why you often see large groups hanging out in the same location in public, all of them head down on their phones. Cuban cell phone plans, provided by, natch, ETECSA, also come with some cellular data. I don’t know how much, but I do know not a lot. Locals seem to use cellular data as an emergency.

I can vouch for that. We use Google Voice, which is VOIP, so we don’t need an actual cellular service. Instead, we use a global data service, Airalo. Except Airalo doesn’t operate in Cuba. The only service we found that does is Gigsky, and the cost difference is dramatic.

With Airalo, we get 20 gigabytes of data that we can use over a six month period for $89. We don’t use anything like 20 gigs of roaming data in six months, so that works out to a very affordable $15/month each to have essentially unfettered global roaming data, which is probably cheaper than your cell plan. The Airalo plan only covers 89 countries, so there will be times when we have to pick up a more expensive plan to close the gap. This is one of those times.

Gigsky’s plan is $24 for 200 megabytes of data over two weeks. That is not a lot of data, and a lot of it gets used just by your phone doing phone things when you turn cellular data on. It’s taken me three $24 data packs to figure out how to use it. Basically like taking a camp shower: turn the water on to get wet. Turn the water off. Soap. Turn the water on. Rinse. Turn the water back off and thank your lucky stars you got a fucking shower. Ingrate.

For the phone, that looks like: turn off Cellular Data globally, for the phone. Turn off Cellular Data for every app on your phone. When you need to look something up using cellular data, turn it on for that app only, then turn it on for your phone. Look up what you need to, and then shut off Cellular Data for both phone and app right away, before your phone does something stupid behind your back.

Our other fix has been to shift to Maps.Me for local mapping, rather than Apple Maps or Google Maps. Maps.Me lets you download full country maps to your phone, so you don’t need to be connected when you’re wandering around. Mapping is probably 90% of what we use while we’re outside (Wikipedia is the other 10%), so that’s pretty much eliminated the need for cellular data.

So if wifi is only the pipe and cellular data is, at best, an emergency method, how do you get data? ETECSA sells it. By the hour. How do you buy hourly ETECSA data? At an official government ETECSA office. Hourly data can be purchased as cards with passcodes, or loaded onto a permanent account. And it’s not very expensive: $25 CUP, about 15¢, per hour.

The permanent account sounds easiest, and our host said we could open one at an ETECSA office. Except we couldn’t. We could never figure out why. Whenever we asked about opening an account, we were just told No. Sometimes with a sad head shake, sometimes without. But always No. We don’t know if they’re not permitted for foreigners or they were just somehow unavailable whenever we asked. And we’ll never know.

The cards come in two denominations: one hour and five hour. But you’re only permitted to purchase three cards at a time, whatever the denomination, so five hours is best. If they have any five hour cards at the ETECSA office. Or one hour cards. They frequently seem to have neither. But the three card limitation is per passport, so Dorothy and I have started going together, to double up.

We’d gone to our closest ETECSA office to be told they didn’t have any cards. Tomorrow? Sad head shake. But we were directed to an office about a 15 minute taxi ride away, and jumped at the opportunity. After waiting in line, because waiting in line, I got three five hour cards. And Dorothy got… two. We appeared to have gotten the last five hour cards and hightailed it out of there before the locals noticed that we’d emptied the vault.

One of the oddities of this whole system, by the way, is the manner in which connectivity is managed. We’re used to bandwidth constraints, but I think that between the slow backbone to Venezuela and the copper to the router, there isn’t enough bandwidth to carve up for meaningful measurement. Which leaves time. But weirdly, once I’ve authenticated a single client to the wifi router, any other client that logs into that router picks up the internet connection. You’d think, since they’re metering time, that it would be device-by-device. Maybe it’s a technical limitation of their router environment, and maybe it’s that multiple clients will still be sharing the same constrained bandwidth, so who cares. Either way, it’s actually nice that we can both hop online to check email and such at the same time.

How long did it take us to figure out how to (more or less) reliably get internet access? About two weeks into our four week stay. But we’re pros now, and everything works fine. Or as fine as it actually works.

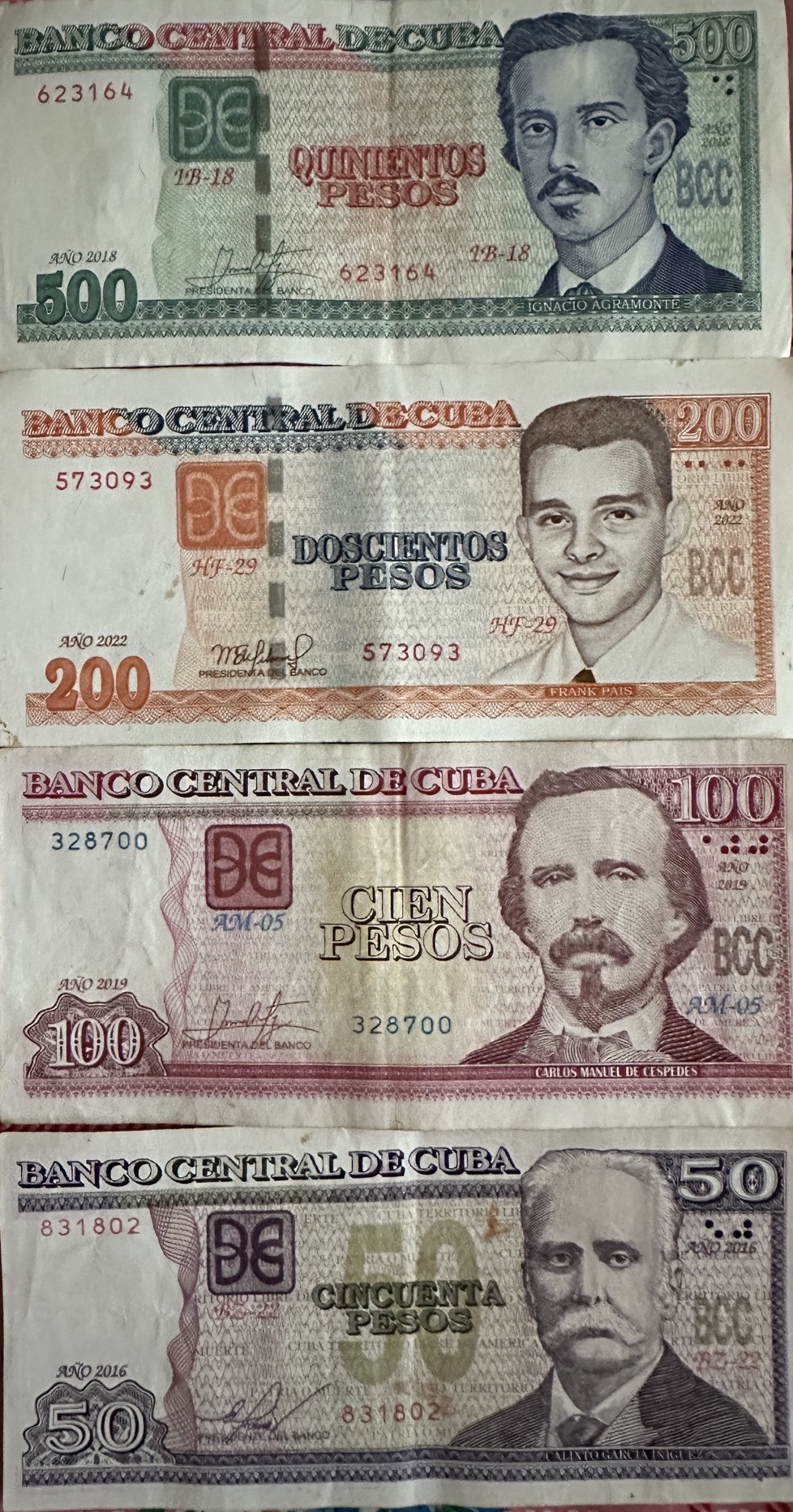

Currency

As complicated as the Internet is, it’s a cakewalk compared to Cuban currency.

Until 2021, Cuba had two currencies: the Cuban Peso (CUP) and the Cuban Convertible Peso (CUC). The CUC was introduced in 1994 after the collapse of the Soviet Union (the Cuban Peso had previously been pegged to the ruble), and was pegged 1:1 to the US dollar. The official exchange rate for the CUP was 25 to the US dollar. While there are many reasons for and impacts of the dual currency system, one of its effects was to create a two-tiered economy. Workers were paid in CUP, whereas foreigners used CUC, putting the value of hard currency beyond the reach of most Cubanos. Businesses with a foreign clientele thus had access to the much higher value CUC.

Curiously, the elimination of the CUC didn’t change things. The two-tiered economy still exists, it’s just enforced by prices. There are goods and services priced for the local economy, and goods and services priced for the tourist economy and those with access to the hard currency associated with the tourist economy.

Taxis are out of reach of most locals, as are most bars and restaurants, although there is cheaper street food that’s pitched towards local consumption. For the higher priced services, prices are expressed in USD or Euros, although CUP can be used (at not the most generous exchange rate). Higher end restaurants will often have menus with prices in USD, and taxis will often quote fares in USD. You can’t use USD for any official business, but it’s coin of the realm in the real world.

Making matters even more complicated, as if that was possible, is the existence of the MLC: Moneda Libremente Convertible (Freely Convertible Currency), introduced in 2019. The MLC is a payment method that uses a special credit card that can be loaded with any currency, and then used to pay for goods and services with shops that accept the MLC card. Which appears to be next to nobody. We’ve only seen one store so far that we couldn’t purchase from because we didn’t have an MLC card. It’s not at all obvious what problem the MLC is meant to address.

Hard currency is in high demand, so while the official CUP-USD exchange rate is still 24:1, the street exchange rate is about 180:1. We’ve exchanged through our host at 170:1, which seems like a perfectly reasonable premium for not having to wander about the streets hoping not to get scammed. While the disparity between official and street exchange rates would seem to create an irresistible arbitrage opportunity, the CUP can’t be exchanged outside of Cuba, and you can’t take more than 5,000 CUP (about $30 at street rates) out of the country.

In addition, the existence of the unofficial foreign currency market has forced the Cuban government to compete. The government now exchanges most foreign currencies at about four times the “official” rate, which isn’t confusing at all. The current official unofficial rate is 120:1, which closes the gap but still leaves an attractive arbitrage opportunity, mitigated in part by the 8% fee the Cuban government charges to exchange USD. All other currencies have a 2% fee. Every dollar exchanged into the unofficial rate and back out at the official rate (which is the only way to turn CUP into USD – the unofficial market has no interest in selling its USD) would yield about a 30% return.

Honestly, I think the only thing that discourages exchange rate arbitrage tourism is the per transaction restriction of about $300 USD and the long bank lines. You could come to Cuba for a 30% return on your dollars, but that’s all you’d be doing while here. Still, I’d wager that some folks come here with that as their primary goal, regardless.

The Economy

Because only some people have access to the hard currency economy (airbnb hosts, taxi drivers, restaurateurs…), inequality is seeping into the Cuban economy. Obviously, nothing at all like the gap in the US, but it exists, and it’s a relatively new feature. It’s not a positive development, and is bound to have more severe negative consequences (e.g. higher crime…) down the road.

What largely counterbalanced the US bloqueo was the economic support of the USSR. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, that all went to shit, ushering in what was known as The Special Period. That special period involved belt tightening and rationing, at both the individual and government levels. Sadly, those conditions are largely the same today as in the 90s. The US embargo has handicapped Cuba’s ability to recover from the loss of their primary patron and trading partner.

The Cuban government turned to tourism as a source of hard currency and economic growth. Tourism is now Cuba’s largest sector, representing 10% of Cuba’s GDP (meaning that the pandemic and the hurricane that followed it hurt Cuba even more than most countries). There’s no small irony in a socialist/communist haven focusing on tourism for survival. Attracting tourists requires providing the basic necessities that the Cuban government has had trouble providing to its citizens. As much as there’s a general understanding that tourism is a huge benefit to the economy, there’s also a great deal of frustration that tourists are prioritized over citizens. It’s tough to live with a five egg/month ration, when every day you pass tourist restaurants serving omelets for breakfast. For more than you can afford.

Other than the bloqueo itself, the other major economic distortion is emigration. The US has created a fast track path for Cubans (as well as Haitians, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans) that eases the immigration process. The net effect of this policy is extractive, and is no different than the US building a mining facility in Cuba to extract some valuable resource. It’s just that the valuable resources are people and intellectual capital, and it doesn’t require getting one’s hands dirty with mines and such. It can be done very effectively and cleanly from a distance.

What happens is that young people are educated in the excellent and free Cuban educational system. When they have their degrees, they then take the knowledge and skills the Cuban government has provided them to the US, where their entry is facilitated and they can make more money. This both wastes the investment the Cuban government has made in these people’s education and brain drains Cuba, depriving the economy of the benefit of their knowledge and abilities.

Amplifying the physical brain drain is the virtual brain drain. Professionals who stay in Cuba are moving into the service economy, for access to hard currency. Doctors, lawyers, and teachers are waiting tables and driving taxis, because it pays better. It’s a perfectly rational decision, but it just adds to the factors hollowing Cuba out.

The bloqueo is strangling the Cuban economy, and has created the conditions under which the best and the brightest want to leave. This is a vicious cycle, in which poor economic conditions induce emigration, and emigration worsens economic conditions. Both ends of this fuckery circle jerk are fueled by intentional US policies.